Neanderthals vs. Early Modern Humans: Childhood Stress Reflected in Dental Growth Disruptions

In a groundbreaking study published in Scientific Reports, researchers investigated the differences in childhood stress between Neanderthals and early modern humans by analyzing dental enamel growth disruptions. The study aimed to shed light on the levels of physiological stress experienced by these two Paleolithic hominin groups.

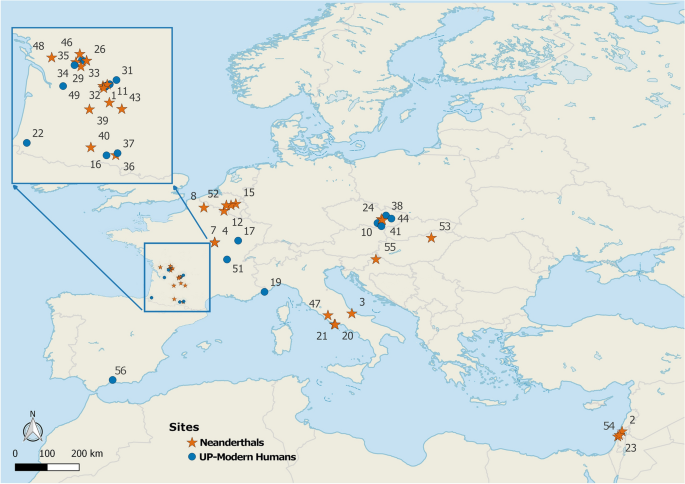

Using high-resolution epoxy replicas of 1048 Paleolithic deciduous and permanent dental remains from various sites in western Eurasia, the researchers examined 867 teeth from 176 individuals. By tracking hypoplastic defects, such as linear enamel hypoplasia (LEH), furrows, and pits, the researchers were able to identify periods of growth disruptions during childhood development.

The results of the study revealed that Neanderthals and Upper Paleolithic modern humans showed a similar overall likelihood of experiencing enamel defects. However, when analyzing the ontogenetic distribution of these defects, distinct patterns emerged. Neanderthals exhibited a delayed onset and peak of stress events compared to early modern humans, particularly during the weaning process.

The findings suggest that early modern humans may have had better strategies to mitigate stress during the weaning period, resulting in lower levels of physiological stress compared to Neanderthals. These differences in stress patterns could have implications for the survival and adaptation of these hominin groups in the Paleolithic era.

This comprehensive study provides valuable insights into the childhood stress experienced by Neanderthals and early modern humans, highlighting the importance of dental enamel growth disruptions as a marker for understanding past populations’ physiological well-being. Further research in this area could offer more clues about the survival strategies and life history of these ancient hominins.

Paleolithic Childhood Stress: Insights from Dental Enamel Growth Disruptions

A recent study published in Scientific Reports delved into the differences in childhood stress between Neanderthals and early modern humans using dental enamel growth disruptions as a proxy. By examining 867 teeth from 176 individuals across various Paleolithic sites in western Eurasia, researchers were able to track hypoplastic defects and analyze the ontogenetic distribution of these enamel growth disruptions.

The study revealed that Neanderthals and Upper Paleolithic modern humans exhibited similar overall likelihoods of experiencing enamel defects. However, when looking at the timing of these defects, distinct patterns emerged. Neanderthals showed a delayed increase in stress events during the weaning process, while early modern humans experienced a peak in stress during this period.

These findings suggest that early modern humans may have had more effective strategies to cope with stress during the weaning phase, leading to lower levels of physiological stress compared to Neanderthals. The study underscores the importance of dental enamel growth disruptions in understanding childhood stress in ancient populations and provides valuable insights into the survival strategies of these hominin groups during the Paleolithic era.

Further research in this area could offer deeper insights into the adaptive behaviors and life histories of Neanderthals and early modern humans, shedding light on the factors that influenced their survival and evolution in challenging environments.

Exploring Childhood Stress in Neanderthals and Early Modern Humans through Dental Enamel Growth Disruptions

A new study published in Scientific Reports investigated the differences in childhood stress between Neanderthals and early modern humans using dental enamel growth disruptions as a key indicator. By analyzing 867 teeth from 176 individuals across Paleolithic sites in western Eurasia, researchers were able to track hypoplastic defects and assess the ontogenetic distribution of these enamel disruptions.

The study found that Neanderthals and Upper Paleolithic modern humans exhibited similar overall likelihoods of experiencing enamel defects. However, when examining the timing of these defects, distinct patterns emerged. Neanderthals showed a delayed onset of stress events, particularly during the weaning process, while early modern humans experienced a peak in stress around this period.

These findings suggest that early modern humans may have had more effective coping mechanisms for stress during the weaning phase, leading to lower levels of physiological stress compared to Neanderthals. The research highlights the significance of dental enamel growth disruptions in understanding childhood stress and provides valuable insights into the survival strategies of these ancient hominin groups.

Further exploration of this topic could offer deeper insights into the adaptive behaviors and life histories of Neanderthals and early modern humans, shedding light on the factors that shaped their resilience and evolutionary success in challenging environments.